Dear Readers,

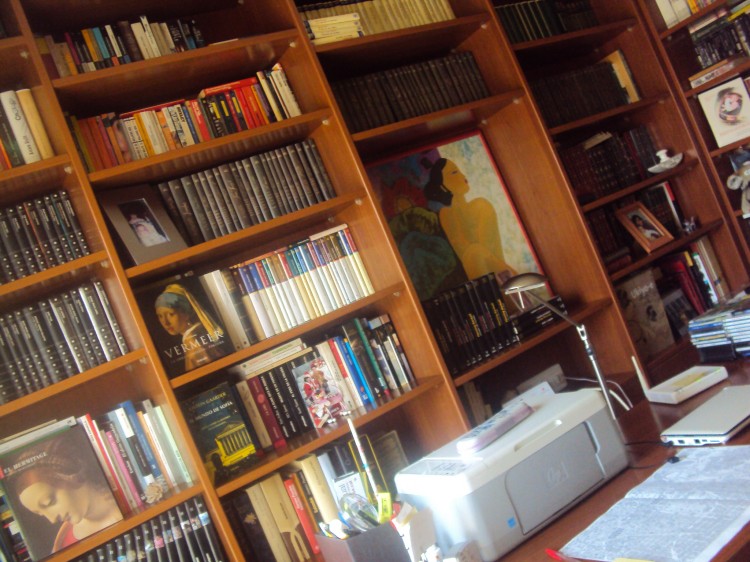

I am writing from my beautiful summer home in Barcelona where I took up a post-PhD thesis writing retreat. The home has an arts library where I find myself reading, writing, and connecting with creative souls. After I read and write, I often seek new paths among Roman ruins, Medieval Gothic architecture, and contemporary art spaces where many heroes and artists received fame.

In my last post, I mentioned my focus on celebrity culture. I have been often asked: what is it about fame that appeals me and calls my attention in cultural studies?

Let us address this question with a positive response, ‘why not?’

Perhaps there is a negative connotation of the word infamy that paradoxically helps to construct fame. One may argue that fans engage in celebrity gossips, rumours, and scandals based on taboo issues. These cultural practices play a sociological function in integrating society on grounds of ethics and morality. Celebrity gossips, then, function as narrative devices to negotiate ideological tensions and manage social norms and behaviour. Indeed, celebrity bashing is a pleasurable practice in fame, but it shifts attention away from merit-based talent that has been characteristic of heroes since historical times.

The construction of celebrities is ubiquitous in modern culture. One can trace historical roots of celebrity culture in the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman eras where hero worship was prevalent. With the Industrial Revolution and rise of mass communication, fame has had a pervasive presence in how fans engage in pleasures and identification, in how they develop para-social relations with celebrities, and ways in which artists understand the production and representation of their own talent in popular culture. Like glamour, fame carries splendour, allure, sexual appeal, and questions of authenticity that can be partially fulfilled only when it remains to be an illusion. While these ongoing questions are integral to the negotiation and maintenance of desire for celebrities, the questions rarely address the talent based on which many public personalities shine higher on their path and become popular to the mass.

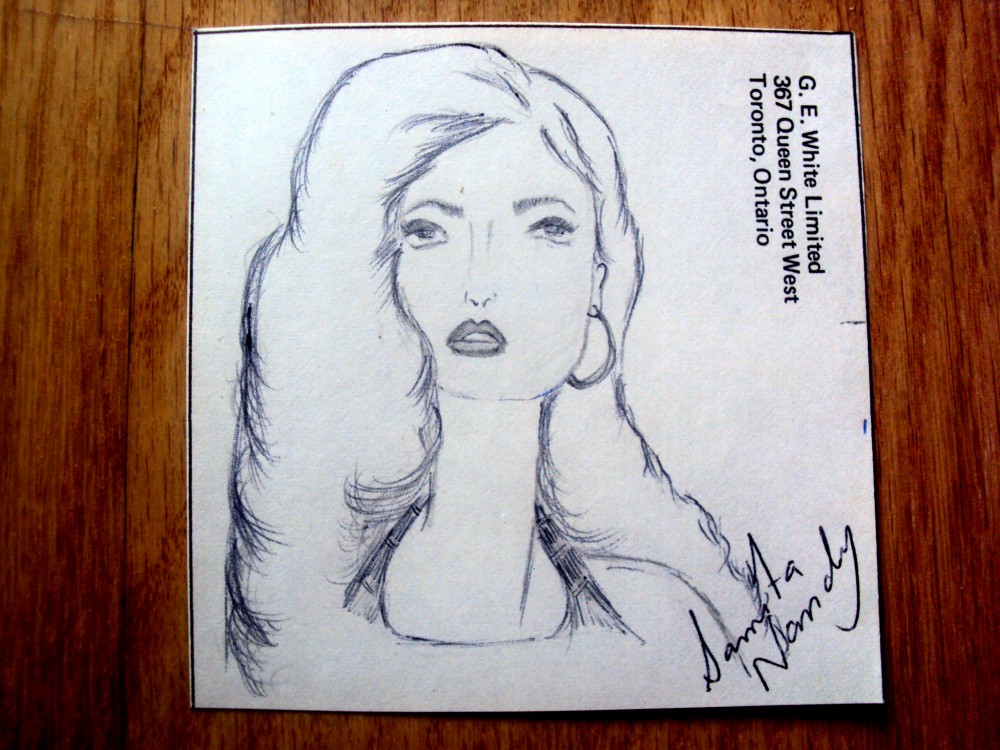

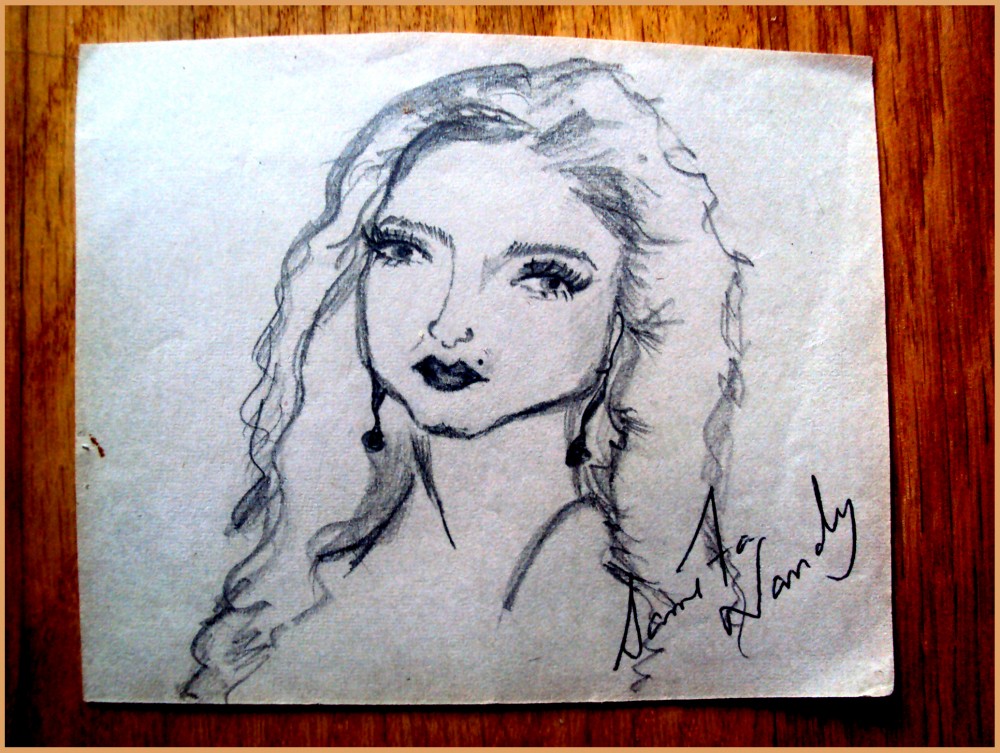

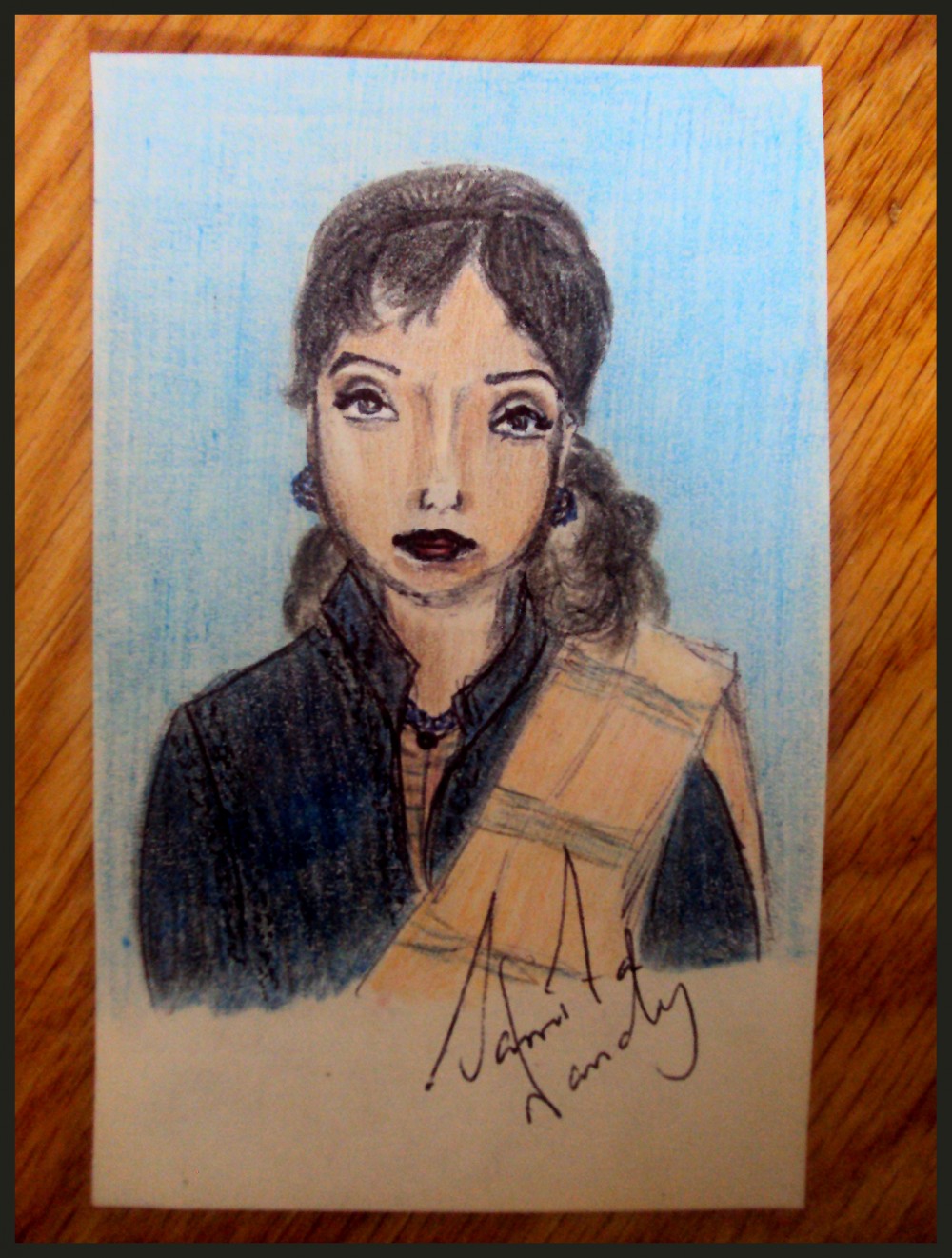

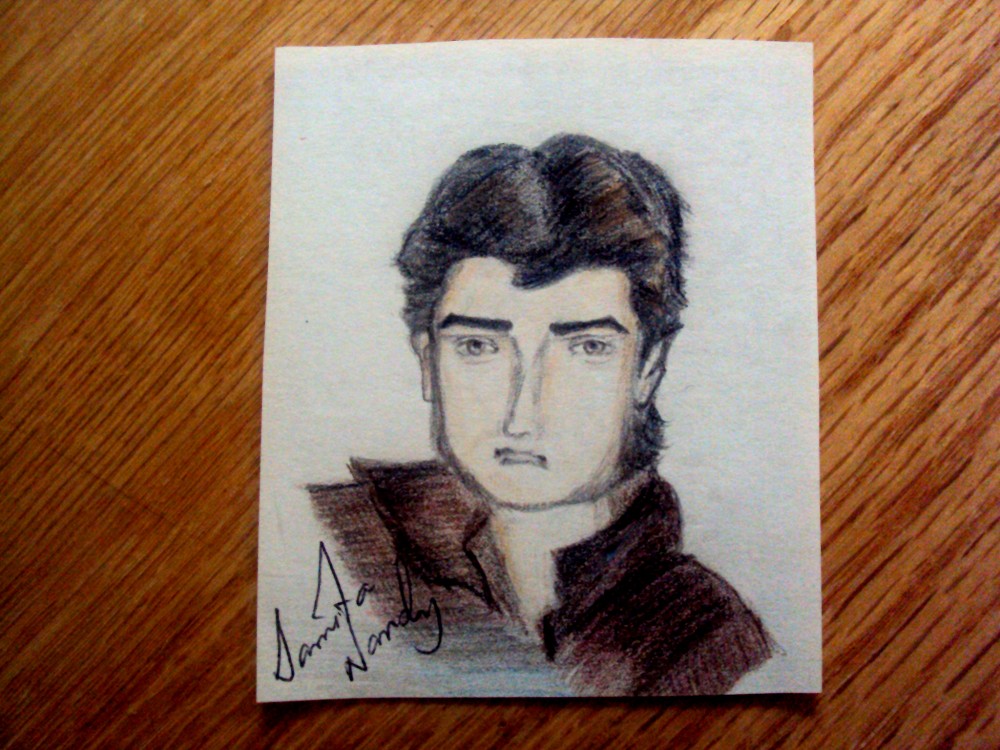

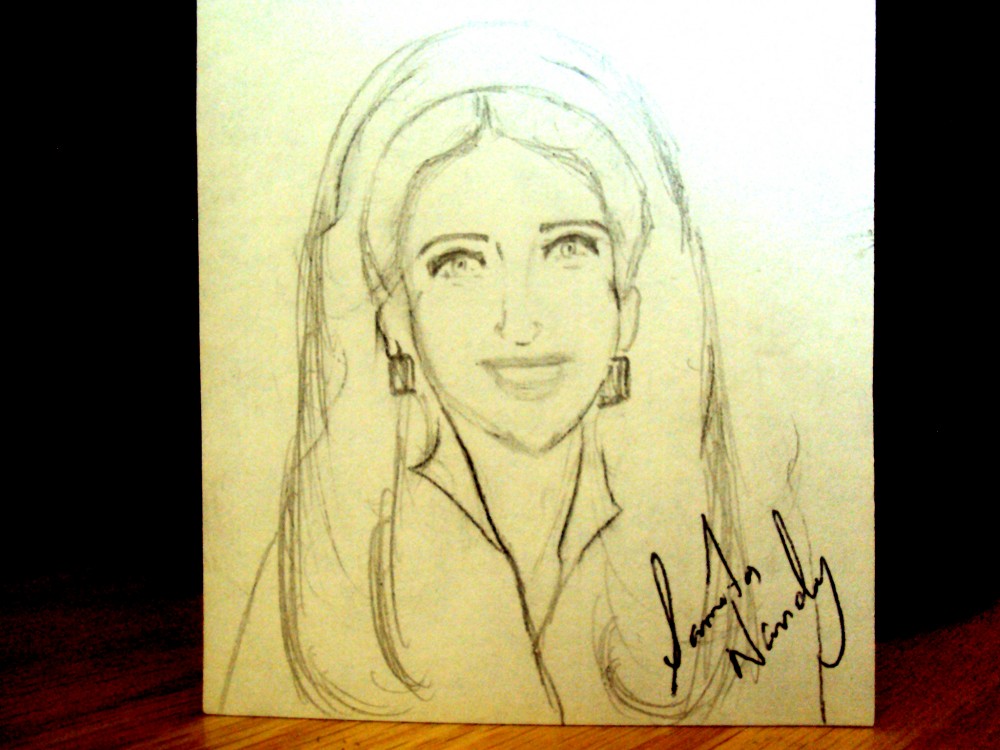

My passion for understanding talent within popular culture goes back to my high school years when I indulged in portrait art and acting. The artistic expression formed an integral part of my thirteen years of journey in India, while carrying a specific sense of individuality from my birth country, Canada. The artistic inspiration comes from my beloved mother Saswati Nandy, who was a beautiful visual and performance artist and a Master’s graduate. I remember her joyfully telling me how she received an offer to be the lead actress in a Bengali film as well as in a dance-theatre on stage, but was not able to pursue performance due to social and cultural repression. I received particular inspiration to sketch artists, especially film-based talents, act, and perform dance movements developed in Bollywood celebrity culture. My teacher and mentor Ronita Mukherjee was highly inspirational and motivational in pursuing art that led to my research. My art was simply an impression of artists (including myself) and hence, part of self-reflection that I exclusively shared with my mother and my mentor.

For me, portraits were a form of representation that connected me to artistic subjects in a self-reflexive manner. At that time, I sketched portraits representing film artists as well as talented companions (e.g., Portrait 4) who demonstrated a passion for arts. While most portraits were based on existing photographs of celebrities in films, others carried spontaneous pen or pencil strokes that drew on my memory of those I considered admirable. In either case, my flair for representing talent and sketching their portraits were an attempt to collapse what can be called the ‘aura’ of distance or the cult value of celebrities that may mystify the talent for which the personalities were initially recognized.

One can draw on Daniel Boorstin and argue that public figures are known for ”well-knowness” (1961, p. 57). James Monaco (1978) further highlights, “Celebrities are, of course, well-known. But people have been well-known, more or less, for centuries” (1978, p. 5). Unlike heroes of the nineteenth century, celebrities now” needn’t have done – needn’t do – anything special. Their function isn’t to act – just to be…To a large extent, celebrity has entirely superseded heroism” (Monaco,1978, pp. 5-6). At the same time, there are celebrities who are well-known for their ‘meritocratic fame.’

Drawing portraits, like writing cultural commentaries, played a significant role in explaining both history and talent in relation to fame-based practices. As Sean Redmond and Su Holmes (2006) suggest, “the process of interpretation, and the construction, selection and processing of evidence” is integral to understanding fame and guides textual productions within it. Redmond and Holmes explain that writing the history of fame and explaining its changes demand self reflection on a celebrity culture in which it is written, both textually and visually. In the process, the writing, like drawing portraits, reflects and reinforces fame in a way that is not static and objective but is a subjective process. As “celebrity only exists within representation,” (Redmond and Holmes, 2006), it is necessary to draw on stories written about celebrities as well as their photographs and performances in mapping the history of fame.

The portraits, like historical texts, became sites of truth and knowledge that have an affect / effect on those who creatively read it. They become a complex set of signs that can be intertextually read in relation to films and photographs that I sketched. Celebrity culture is, then, not limited to the performances of famous personalities within popular discourses, but includes artefacts that historicize it and explain its changes within a self-reflective framework. Fame-based practices respond to the demands of self-reflectivity and carry a combination of celebrity texts (e.g., films, posters, photographs, journalistic reports, portraits) that are intertextually read and understand in relation to each other.

My portraits explored original ways of understanding talent that is often commodified in technological reproductions and may distance an artist from their artistic communication. As an amateur portrait artist, I wanted to seek both external as well as the internal appearance of talented figures and restore a sense of art that was specific to the artistic subject portrayed in media as well as the artist within me.

I went back to Canada and started studying media in my honours and Masters degrees at York University in Toronto. During this academic journey, my mum suddenly passed away. I painfully lost many other loved ones in life, but her loss has been the most traumatic experience. I was two weeks away from my Masters defense for which she was guiding me. My heart still breaks into pieces and I have tears in my eyes when I feel her presence in memories, imaginations, and dreams. However I buried my pain and grief in her strength and passions. Within two weeks of her loss, I defended my Masters and chose to strengthen ways to communicate talent as an innate force of life. I chose to ‘re-live’ with art and writing while communicating from a position of deep, personal loss. I took up broadcast journalism, documentary filmmaking, and teaching media and communications at the University of Toronto. In classes, I found myself sharing and supporting the talent and communication of hundreds of students who had creative paths to explore and express something unique to all.

While I was teaching, I found myself shifting from portrait art to biography films. With a creative team in Premiere Cinematic Productions, I directed and produced a documentary that portrayed media and arts personality Tushar Unadkat in popular culture. The film Frame by Frame: Tushar Unadkat focussed on his talent as well as the social and personal context in which he broke boundaries and started to shine on his path. The biography, like my portrait, spoke with a visual language that aesthetically overlapped with symbols of celebrity culture and was situated in contexts in which popular recognition often forms.

The journey in creating and understanding my portrait art and biographies demanded further attention. It appeared that there was a strong need to understand specific contexts and the complex interplay of media, businesses, government, and audiences in the mass production of talent in popular culture. I was finally able to examine this interplay as I mapped the process and implications of specific fame-based practices in my Doctoral research. I received two full time grants valued at $120,000 and completed the research with the incredible support of many individuals and cultural institutions in both Canada and Australia.

In academia and cultural productions, there is a limited attention to meanings of fame and how talent is often related to it. A deeper understanding of it fills a major gap that Graeme Turner identifies in studies of celebrity culture. Turner points out that most academics have focused on celebrities as representations and effects of discourses. Like journalists, academics have focussed on individual celebrities as visual and literary texts, but not their industrial production at a structural level. Turner argues for a strong need to establish a base for studying industrial production of celebrities and integrate modes of analysis that are not limited to textual and discourse analysis. The study of industrial production is important because it contributes ways of understanding the celebrity as a commodity that supports political and economic developments of brands. In the process, it helps to reveal strategic and aesthetic ways in which its hidden art and talent can be restored and recognized beyond social structures of our commodifed culture.

The academic and artistic journey of understanding the production and representation of talent in popular culture has a long way to go. Meanwhile, finding one’s distinct path and celebrating it beyond the economic and political structures is an important task – it is an ongoing process. When fans love celebrities, it is often not because of the same beaten paths that they have taken. Many adored personalities are talented artists who have passionately listened to their selves and broke boundaries of the collective ‘Other,’ while subject to the same social structures in which are all born.

To shine as the brightest star, it is important to find and strengthen our unique path that is meant to be different from others. When we critically listen to ourselves, the answers are inside and around us. Every individual bearing meritocratic fame now and hero from the past received those answers. There is a love in the passion and desire to brighten the path.

My next post from Toronto will reflect on literary texts in celebrity studies and what we can learn from well known academics and artists. What are some of the working methods for their success in creative arts?

Till then, keep creating and sharing your shining path with love!

With affection from Barcelona,

Samita

© 2012 Dr Samita Nandy. All rights reserved. Texts and images on this site cannot be copied, used or reproduced for any academic or commercial purpose without written permission from Samita Nandy.

I love your sketches and your enlightening writing!